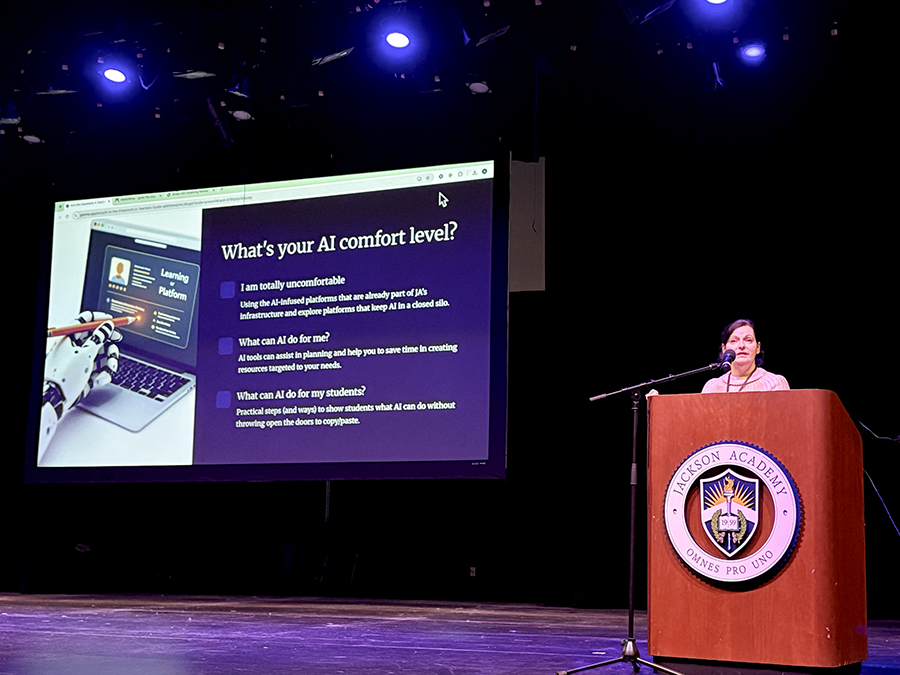

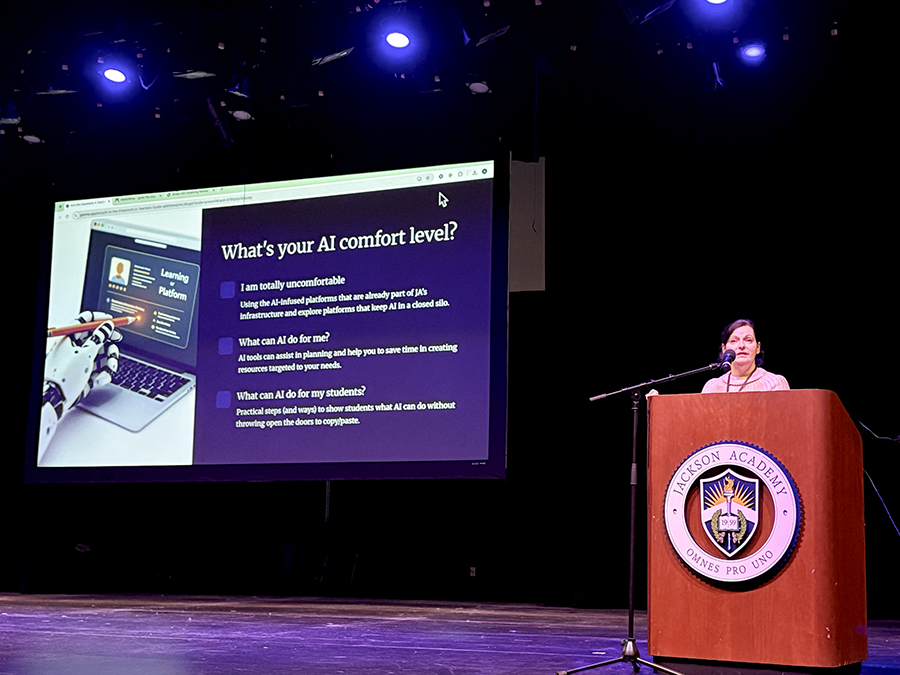

Faculty and staff of Jackson Academy heard a fascinating presentation about artificial intelligence in education on Professional Development Day in March. Literature teacher Alesha Cary led a session that she has presented at professional conferences in Mississippi on what educators should understand about AI, both the positive and the cautionary.

Cary pointed out to educators that AI is built into many of the programs that are familiar to educators, such as Vocabulary.com; Kahoot; Edpuzzle (allows the teacher to embed questions into an educational video); Google (with searches powered by AI); Quizizz (a quiz builder); and Blooket (an educational game platform).

She described the benefits of platforms that offer ethical and robust AI features that she considers as teacher-centered. She is careful to choose those that are designed for education or have safeguards built into their systems as opposed to popular platforms that have fewer guardrails in place. For example, some platforms share data entered widely, while others do not share the educators’ data at all.

One teacher-centered platform she enjoys using is TeacherServer, developed by and for educators. “They have a strict data policy that is siloed so your data is not shared with other commercial interests as it is when you are using ChatGPT,” she explained. “TeacherServer tends to remember your methods the more you work with it individually.” She also noted that it is grade-level aligned and can pull from your class standards, the Mississippi state standards, and others.

A platform she recommends that is a large language model like ChatGPT is Claude by Anthropic. “All AI is not the same,” Cary said. “While ChatGPT is more likely just to answer your question, Claude keeps copyright and ethical considerations in play, prompting you as a user when you are getting too close to crossing the line.” The system asks the user questions and brings appropriate use of information to the user’s attention. “That is a helpful guardrail,” Cary says.

Cary demonstrated ways in which the incorporation of AI features enhances student learning. For instance, using the free version of Google Notebook LM, she developed a study guide for Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, including a timeline and characters, themes of the book, and a list of resources. She also provided Notebook LM with details from the book and asked it to create a podcast, giving students an entertaining overview of the book based on the information she had vetted. With the podcast, students were less likely to access shortened resources like SparkNotes. An added bonus to the Notebook LM’s podcast feature is the ability to interact with the “hosts,” asking specific questions about the content. “As a review and study tool, this is an incredible resource for a student who is struggling with the material, and since the ‘hosts’ responses are controlled by the material I’ve provided to the Notebook, students will receive accurate and targeted help.”

She also enjoys using Brisk, a Google-based extension for teachers that provides the students with automated feedback on their mastery of learning objectives that the teacher has set. “Students chat with the tutor, and it measures whether they have met the learning objectives,” Cary said. “With programs like Brisk and SchoolAI, teachers can set academic goals and objectives and have the students interact with content. Teachers can review the individual student output, along with the data reports from the AI programs to determine which students are truly mastering the content, and which students need more help.”

AI programs are increasing the number of ways teachers can help students with different learning styles. Programs also help teachers develop learning modules that engage students in activities that reinforce learning.

“AI is allowing teachers to design something that meets the needs of individual learners. Its capacity makes the idea of designing something for the individual a reality,” she said. As education tests AI, teachers work to address plagiarism challenges, information reliability, skills development concerns, and strategic responses for teachers. “This technology is part of the landscape, and it comes with definite positives and negatives. If we choose to focus only on the negatives and challenges, we do our students a disservice. We must acknowledge those, yes, but they only become the central focus of the story if we allow them to do so.”

Cary closed her talk with a personal story that resonated with the JA audience. As a fourth grader at Bearss Academy, Cary met the man who was instrumental in founding Jackson Academy in 1959. A proponent of phonics, Bearss had experienced great success teaching students to read with his method. Reading was why she came face-to-face with Bearss one day in his office after she told her teacher that a book about a dog was stupid (her dog had died the week before).

After staring at her intently, Bearss asked the fourth grader what she wanted to read. The answer was Shakespeare. He produced The Tempest, and with that book and the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, she began reading and recording every word she did not know, writing the full definition and sentences with each unfamiliar word. She filled a notebook and a half. While she does not remember much about The Tempest, she remembers the rich vocabulary she developed from the experience.

“I look at that moment as a moment who made me who I am,” she said. “He saw me as a person and designed something for me. It turned me into a teacher, and I will forever be thankful for that.” With mastery of her subject and the judicious use of AI, Cary is designing learning experiences for her students that she hopes will one day direct them to their calling.